Chapter 1: West

Salmon are an iconic species of Canada’s West Coast. They play a critical role in supporting and maintaining ecological health, and in the social fabric of First Nations and tribal culture. Rich salmon fisheries sustained communities here for millennia.

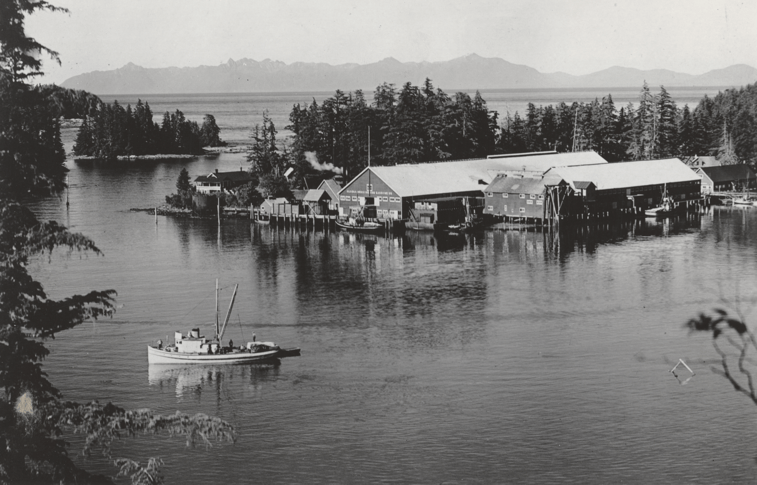

Salmon is a delicious, highly nutritious, and highly desired fish. In the late 19th century the wealth of salmon heading up BC’s coastal rivers began to attract modern capital, and with it fisherman and cannery workers from around the world. For the next hundred years British, French, Greek, Chinese, and Japanese immigrants and their indigenous counterparts made salmon fishing one of BC’s most important economic engines.

Types of Salmon

-

Chum

Most common species

-

Pink

Most abundant,

also known as ‘Humpies’ -

Coho

Most sought after species

-

Sockeye

Most colourful and can

survive freshwater -

Chinook

Also known as the

‘King Salmon’

The Salish Sea is home to five different species of Pacific salmon.

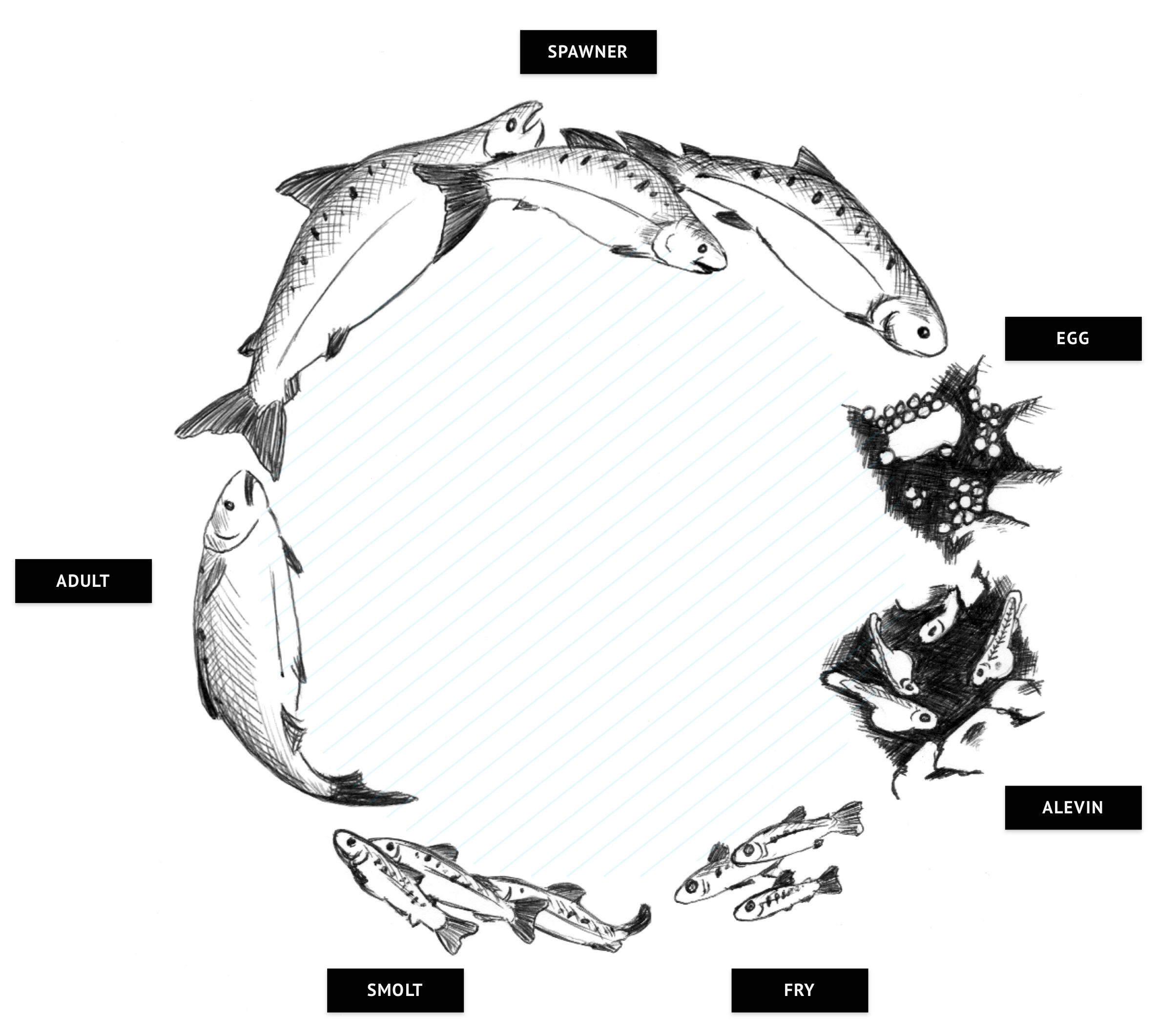

Salmon Life Cycle

Salmon are are born in fresh water, spend much of their life at sea, and then return to fresh water to spawn. They die after spawning once. While all salmon follow this life cycle, the amount of time spent in each part of the life cycle can vary greatly from species to species.

Chinook names

Chinook salmon are known by many names throughout the Salish Sea and around the world.

- Blackmouth (USA)

- K'with'thet (Salish)

- K'wolexw (Salish)

- King salmon (USA, Canada)

- Oncorhynchus tshawytscha (Latin)

- Sa aeup (Nuuchahnulth)

- Sa-cin (Nuuchahnulth)

- Schaanexw (Salish)

- Shamet skelex (Salish)

- Shmexwalsh (Salish)

- Sinaech (Salish)

- S k'wel'eng's schaanexw (Salish)

- Slhop' schaanexw (Salish)

- Spak'ws schaanexw (Salish)

- Spring salmon (USA, Canada, Australia)

- St'thokwi (Salish)

- Su-ha (Nuuchahnulth)

- Tyee salmon (Canada, USA)

Dan Hayes sets out to explore the issues facing salmon, beginning his journey with a look at the importance of wild salmon habitats.

Why is salmon an important food?

Salmon provide food for a variety of wildlife, from bald eagles to killer whales to grizzly bears. Because salmon die after spawning, their carcasses also provide abundant food and nutrients to plants and animals, including tiny aquatic insects and other invertebrates that in turn provide food for other animals.

During their life cycle, salmon transfer energy and nutrients between the Pacific Ocean and freshwater and land habitats. In areas that have experienced dramatic declines in salmon, there is a measurable deficit of nutrients to help support the ecosystem.

Economic Impact

Commercial salmon fisheries in the Salish Sea were worth over $59 million in 2010, driven by an unusually high catch rate that year. From 2003 to 2009, the value ranged from $12.6 to $31.5 million.

Commercial Value of Chinook Salmon Fisheries

Annual employment in commercial fishing industry is highly seasonal. In BC, employment related to commercial fishing was estimated at 2,100 in 2005 - the lowest number recorded in the past two decades - and peaked at 7,000 in 1989. The BC fish processing industry employed 3,700 people in 2005, and peaked at 6,000 in 2000.

In Washington, employment related to commercial and recreational fisheries (including harvesters, processors, distributors) was estimated at over 23,000 people in 2009.

In 2005, sport fishing in BC generated $248 million, plus an additional $46 million through associated activities.

Recreational salmon fisheries in the Salish Sea also play important economic and social roles for residents and visitors to the region. Chinook are among the most prized recreational fish. In 2005, sport fishing in BC generated $248 million, plus an additional $46 million through associated activities - such as shopping or visits to other attractions by visiting anglers. Sport fishing-related activities employed 7,700 in BC in 2005, making it the single largest employer in the fisheries and aquaculture sector.

In Washington, recreational fishing in Puget Sound is conservatively valued at $57 million a year. In 2009, the number of jobs directly linked to recreational fisheries was estimated to be over 3,500 people - supporting over 200,000 resident and visiting anglers.

Population Decline

Chinook salmon populations are down 60% since the Pacific Salmon Commission began tracking data in 1984. So is every other species of salmon.

Why is it happening?

The steep decline in salmon is associated with three main factors:

Salmon are easily impacted by changes in habitat. Salmon stocks have decreased as logging, agriculture, and urbanization have impacted their wide ranging habitats.

Dan learns about the limits of the salmon’s habitat and confronts problems associated with open-pen aquaculture.

What is being done to help?

- The Pacific Salmon Treaty

- This agreement, made between Canada and United States in 1985, brought a science-based approach to international salmon conservation. Its goals were to lessen the impacts of harvest reductions, improve our understanding of salmon stocks, and implement individual stock-based management fisheries.

- Wild Salmon Policy

- In 2005, Canada’s Department of Fisheries and Oceans implemented a policy to safeguard the genetic diversity of wild salmon populations, maintain habitat and ecosystem integrity, and manage fisheries for sustainable benefits.

- Licence Retirement Program

- In 2011, Canada’s Department of Fisheries and Oceans launched a program to reduce the number of fishing operations within the Canadian portion of the Salish Sea, with the goal of reducing the number of wild salmon harvested.

- Salish Sea Marine Survival Project

- This research project brings together U.S. and Canadian experts from government, First Nations, and academic and nonprofit organizations in order to improve our understanding about the weak survival rates of juvenile salmon.

Salmon Aquaculture – Solution or Nightmare?

As salmon stocks began to seriously decline in the 1950s fishermen, government, scientists, and entrepreneurs began looking for a way to create a steady and sustainable supply of the fish.

The first fish hatcheries developed in the province weren’t very successful, and were criticized for being little more than PR stunts aimed at placating a concerned public, but by the mid-70s they, and experimental fish farms, were beginning to produce results. By the mid-1980s aquaculture was an emerging industry that has since grown steadily.

Today, the BC Salmon Farmers Association (BCSFA) represents 50 businesses and organizations throughout the value chain of finfish aquaculture in BC. BCSFA members operate an estimated 106 of the 109 licensed and tenured finfish aquaculture facilities, and harvested 78,000mT of salmon in 2016.

Local and global growth

The growth in aquaculture has not just been in BC, but around the world.

Global Aquaculture

Relative Contribution of Aquaculture and Capture Fisheries to Fish for Human Consumption

Today aquaculture produces half of all fish consumed by humans.

There is currently much controversy about the ecological and health impacts of intensive salmon aquaculture. There are particular concerns about the impacts on wild fish and other marine life and on the incomes of commercial salmon fishermen.

Dan visits West Coast FishCulture to investigate the benefits of closed-pen aquaculture.

Two ways to farm salmon

Closed Containment vs. Open Ocean

In the past 30 years, most fish farms have used open-net pens or cages submerged in the open water. Scientists and conservationists call this a high-risk method, because waste, chemicals, parasites and disease can move freely between the net and the ocean or fresh water. Sometimes non-native fish species escape and cross-breed with local populations. The farms also attract large predators, which can get tangled in the nets.

Closed containment systems offer one solution to these problems. Tanks can sit on land or in the water, and a solid wall barrier prevents any interaction between the fish and the natural environment. A recirculation system keeps the tank water fresh, while safely eliminating waste. Closed systems reduce pollution, escapes, diseases and wildlife damage – and can provide a sustainable way to farm fish including salmon, sturgeon, striped bass, and Arctic char.

Sustainable perspective

First foods ceremonies are one way Coast Salish communities celebrate respect for the earth. In spring, families celebrate the first Chinook salmon caught with First Salmon ceremonies called Thehitem (which meanslooking after the fish.) At the end of the ceremonies the bones of the salmon are returned to the river with a prayer giving thanks to the Creator, Chíchelh Siyá:m, and the salmon people. This is to show that the salmon were well-treated and welcome the following year.